One Hundred Days of Resistance: The Not-So Mexican, but Otomí Hope.

♥ Esta crónica periodística está disponible en español, por favor haz click aquí 🙂 https://rip.mx/cien-dias-de-esperanza-otomi/

The Indigenous Peoples National Institute (INPI) looks different – say, more joyful and carefree. On October 12th, 2020, the Otomí community based in Mexico City took over its facilities to make visible the health, education and housing demands of their community, unfulfilled for more than 25 years. They also seek to expose the decisions that are being taken by the current government of the so-called “Fourth Transformation” because, they clarify, “they are mutilating the life and future of many of the Indigenous nations in Mexico.” One-hundred days after the taking over the institute’s headquarters, the Otomí peoples in resistance make a specific call to the public agenda, to let the public know that Indigenous peoples continue to be murdered, outraged and used as a bargaining chip.

1.

The Broken Arm

Inside the office of the Indigenous Peoples National Institute’s Director, Adelfo Regino Montes, you can see wonderful works of art such as vases, fine yarn tissues, hand-carved chests in fine woods, and beautiful, virtuously-manufactured shawls and hats, as well as mezcals of the most diverse and fine agaves. This is an authentic museum of masterpieces made by the native peoples who sent them to Adelfo Regino as offerings, so that he does not let them die in oblivion. However, Indigenous peoples are very much still framed in misery, even though they not only think about their everyday survival, but also about the health of the Earth (both with a capital “T,” in Spanish, as in Earth, and a small “t” – as in land), that is, they defend organic planting, their reclaimed land, the cornfield’s horizontal information and handling, and the knowledge of uncontaminated seeds, since defending all that for them, as well as springs, rivers and lakes, means thinking about the wellbeing of Planet Earth, everyone’s home.

Inside that huge office and behind Regino’s personal desk, there is a wall with shelves where a plaster figure of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) in copper color is perched and displayed. He is smiling both gladly and solemnly, with his presidential sash, in remembrance of his Inauguration Day – I suppose all his other Cabinet members and government officers have in their offices. This peculiar statuette in the manner of a presidential Oscar, has a peculiarity that immediately catches my attention: it’s maimed, with his right arm being broken – that same limb that AMLO stretched out to take a formal protest as Constitutional President of the United Mexican States (“So be it, or else, the people should demand it!”). The broken arm is not missing but perched in front of his feet, as if waiting for someone to apply some glue on it and put it back to the logical place in his cast anatomy.

Statuette reflecting AMLO’s Inauguration Day. Photo: Luis Alberto González.

“His arm fell off, that’s how we found it when we took over the facilities,” says Diego García Bautista, founder of the Emiliano Zapata Benito Juárez Popular Revolutionary Unit (UPREZ), and the Café “Zapata Vive”, social organizations with which he has accompanied for more than 30 years this Otomí community residing in Mexico City, although originally from Santiago Mexquititlán, Querétaro. From these collectives, he has demanded legal mechanisms assuring the community access to health care, education, work and decent housing, which to date, the government has not formally ratified, even though the fourth article of the Mexican Constitution says that “every family has the right to enjoy a dignified and decent housing” and “that the law will establish the necessary tools and support to achieve this goal.” This Otomí community has been demanding compliance with this right for three decades, but they feel now obliged to put that in second place, prioritizing what they consider to be something more urgent: the imposition of mega-construction projects such as the so-called Mayan Train, the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the Hydroelectric Dam in Huexca, Morelos, which for many Indigenous nations are monuments of death and murder.

February 20, 2019, was a date that confirmed the urgency of the previous National Indigenous Congress’ call: Samir Flores Soberanes, one of the most beloved and great defenders of the Nahua territory, and an activist against the thermoelectric and the “Morelos Comprehensive Project” (a pipeline) which various specialists in energy have pointed out as unfeasible and dangerous, was murdered. A project that López Obrador qualified as “of territorial ordering, infrastructure, economic growth and sustainable tourism.”

Samir, a member of the Front of Peoples in Defense of Land and Water (FPDTA) in the states of Morelos, Puebla and Tlaxcala, and the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) was assassinated shortly after a rally in which the president announced a consultation to put the thermoelectric into operation. Samir pointed out that the president was “killing the ideals of Emiliano Zapata.” AMLO interrupted his speech to refer to the protesters as “radical leftists”, and said that “they were nothing else but conservatives” to him, causing outrage in the community. AMLO reaffirmed that even if there were protests, a consultation about the plant’s construction would be carried out, anticipating that his government was in favor of the project.

Otomí people protesting against the attacks to Native peoples due to the imposition of mega-construction projects. Photo: Diego García.

For many Indigenous nations, this was the proof of what the Zapatista communities had been already warning about for a long time, when they denounced harassment from paramilitary groups like the Chinchulines and the so-called Orcao (Organization of Coffee Growers of Ocosingo), as well as of the Green Ecologist and Morena parties, who control the region. Orcao set fire to two of the Zapatista coffee warehouses on August 22, 2020 in the community of Cuxuljá, municipality of Ocosingo in Chiapas. These warehouses are crucial for the survival of the community.

We knew and we know that our freedom will only be the work of ourselves, the original peoples.” Zapatistas stated [about the murder of Samir Flores]. “With the new foreman in Mexico, persecution and death didn’t stop. In just a few months, a dozen comrades from the National Indigenous Congress-Indigenous Government Council, social fighters, were assassinated. Among them, a brother highly respected by the Zapatista peoples: Samir Flores Soberanes, killed after being singled out by the foreman who continues implementing the neoliberal mega-construction projects which obliterate entire villages, destroy nature, and turn the blood of the Native peoples into profit for Wall Street.”

Samir left a deep void in the soul of the Native peoples. “Talking about his death hurts our hearts,” says Maricela Mejía, Councilor of the Indigenous Government Council (CIG) for the Otomí community. This is so because they met this defender of the earth (with uppercase, and lowercase letters, as in Earth and land respectively) very closely. They describe him as a loving father of four children, elementary-school teacher, farmer, peasant, blacksmith, sign maker, computer science graduate, horse rider, radio player, broadcaster, bass player in a Northern music group, and defender and researcher for the viability of organic planting, so as not to continue poisoning the land.

I had the opportunity to meet him one day in Amilcingo, during a wonderful meeting. Samir had really that strength that you simply perceive beyond a gaze, a deep energy that makes humility, conviction and firmness contagious. Then, there was his word so well spoken – sung as if it were music.

Let us understand that defending the land is not just defending those below, but also those above, behind and ahead, those in the middle and on the sides,” he told me. “Why is it so difficult to understand that we must leave behind us a healthy land and healthy human beings, who think and feel the earth? It is the only way to build possibility “.

A girl asked him, “Teacher, when are we going to sow?” “Soon,” Samir replied, and continued telling me, “We usually take a plant to the ravine to instill in the children the culture of sharing. They are often taught to work individually. ‘Hurry up and do what you have to do, and leave the others behind if they don’t do the homework. Just do your thing,’ they are told. That’s how they begin to individualize, losing the sense of belonging to the community, to collective work. So we don’t have much to share. However, with a plant and its sowing, we have a lot to share, thinking about the future and the common property.”

Perhaps the broken arm of the statuette of the president weighed too much, being that on December 1, 2018 (when he was inaugurated as president) one of the main points of his speech was that his government would look at and defend the native peoples of the country. He even participated in a ritual, where leaders of 68 indigenous peoples (coordinated by Adelfo Regino Montes) passed him the sacred smoke of copal and gave him “the baton of command,” becoming the first president in Mexico to perform this type of ritual as a symbol of giving the Indian peoples an important place, acts that had already been performed by leftist governments such as Evo Morales (Bolivia), Rafael Correa (Ecuador) and Juan Manuel Santos (Colombia), and which at the same time represent a political capital sustained by different systems and politicizations of hope.

Samir Flores Soberanes

AMLO has a double indigenist discourse with showoffs of radicalness, such as the liberation of political prisoners who had been 50 years in prison for defending their springs, and the political will for the iconic case of the 43 disappeared students from Ayotzinapa (he knows well that meant the defeat of his predecessor Enrique Peña Nieto, and it has also become a demand for global justice because the case represents the greatest crime of the State in a democracy; AMLO is aware that if he wants to vindicate the policy of the Nation-State, he will have to solve it) but on the other hand, he allows this type of mega-construction project. Due to the insufficient infrastructure of energy sources to ensure service for an overwhelming population growth, the country needs infrastructure, but he is not taking into account more sustainable and horizontal forms to develop these projects. AMLO only wants to see one way and not the many others that various specialists in the field with extensive experience have proposed to him. These one-way-only solutions represent just the tips of icebergs that do not pay attention to the bottom, addressing just “the tip” of the ice, without solving the base of the problem (a classic example is how they solve mobility in cities – instead of motivating effective and sustainable transportation policies, they continue to choose very expensive infrastructure to “attenuate traffic”, which, after just a couple of years, end up all becoming paid parking lots).

Following the PRI book, they don’t think about prevention, but just the pure and cheap political aesthetics of empty solutions. This government, as others have done, responds to the interest of some businessmen who sympathize with an unsustainable over-exploitation of resources, including turning the entire Mexican Southeast into a big Cancún resort area. They do not listen to the crude testimonies of the Caribbean communities that, from the very first line, describe the immeasurable cost in environmental terms and public safety that this means. * [These testimonies (in spanish) of the Peninsular Maya People can be obtained by accessing: http://indignacion.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Boleti%CC%81n-Tren-Maya-tras-la-consulta.pdf]

In the case of the Huexca Thermoelectric Plant (Morelos), protected by the National Guard, it is a mega-construction project that creates poisonous ozone, methane gas, and noise pollution that has produced vomiting, headaches and alterations of the nervous system, especially in children of the community. Not to mention the very high risk it represents for being built in a volcanic eruption zone, since it is located on the slopes of the Popocatépetl volcano: the tenth most active volcano in the world.

On the other hand, the University Seminar of Society, Environment and Institutions of the UNAM (SUSMAI), described in detail that there is a gas pipeline fractured by the September 19, 2017 earthquake of 7.1 degrees with an epicenter in the very Morelos State. This project is also irreversibly destroying the historic river that was navigated in the past by the Insurgents to successfully end the siege of Cuautla, which was crucial for the Independence of Mexico. Specialists say the government has refused clean energy options (photovoltaic) and local participation. Instead, it has favored a national consultation accentuated in towns where people are uninformed on the subject and geographically distant from the problem. On the other hand, specialists point out that 85% of the gas supply for the plant’s operation comes from Texas, a fact that increases fracking in that region. Also, the operation of the plant costs 5.3 billion dollars (8 times more than with clean energy) and 500 million liters of water a day, leaving the Huexca community without the vital liquid.

AMLO and Adelfo Regino Montes. Photo: Luis Alberto González.

2.

The Otomí Resistance

The Otomí community migrated to CDMX, mainly from Santiago Mexquititlán, Querétaro, fleeing like other groups of migrants and refugees from extreme poverty, and trying to find opportunities for survival. Upon their arrival in the capital, they immediately came across a world that marginalized them: authorities, institutions, schools and passers-by in the city, they all acted with unscrupulous discrimination against them. They lived in markets, terminals, subway stations, and outside of restaurants. Always looking for a barely safe place where they could at least wake up the next day, terrible things happened to them, like “a case of a sister who slept on the street and someone took her son from her. It is, of course, very hurtful for her to tell this story. She was asleep. They took her son from her and she never found him. There are many other terrible stories like this, about abuse and robbery,” Councilor Maricela emphatically says. Necessity made families in the same situation meet and unite to protect each other. That is how they found completely abandoned properties located on 1434 Ignacio Zaragoza Avenue, as well as on 74th Zacatecas Street and 200 Guanajuato Street in Roma Neighborhood; and in 18 Roma Street and 7 London Street, in Juárez Neighborhood, where 43 apartments collapsed because of the 1985 earthquake and where unfortunately 95% of its inhabitants lost their lives. The property was deserted and forsaken and the Otomís started gradually fixing the site as much as they could in order to have a settlement where to live. They frequently invited public officers from the Cuauhtémoc County so that they could evaluate the status of the place and they could reach a legal agreement to occupy it as a home. Only one top officer in 1997, Jorge Legorreta, really listened to the community and provided sheets, water tanks and other supplies, so that they would have the minimal conditions for survival. Over the last decade, the property has been subject of a legal dispute, not because of the families of those killed by the earthquake (only two of them claimed their right and accepted the expropriation of the land for the Otomí community in exchange of their fair share in money) but rather from real-estate groups that began to be interested in the Roma Neighborhood properties because of their desirable location. However, they do not have any legal recourse to make them their own.

In their 30 years of organization, the Otomíes have supported many popular causes related to the dignity of Native peoples, one of the most recent being María de Jesús Patricio, a woman from the contemporary Nahua community who was elected as speaker of the Indigenous Governing Council (CIG) and the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) towards an independent candidacy for the presidency of Mexico in 2018, with the aim of making Indigenous peoples able to have a voice in the most important decisions of the country.

In the consultation made by the peoples to get enough signatures for that candidacy, Marichuy – as she is affectionately known – was the candidate who obtained the most honest rubrics with almost 94% legitimacy, showing that the process was transparent, consensual and organized. Although she did not achieve the main objective of obtaining a candidacy from the Indian peoples for the presidency of the Republic, she left many positive things; including 94% of anti-corruption, anti-impunity, not selling, not giving up rates.

Otomí Council Maricela Mejía at the CIG; Speaker María de Jesús Patricio and Council Filiberto Margarito. Photo: Diego García.

After this experience with Marichuy, and recapping the process, the Otomí community was part of the agreement for the emergence of what is known today as the Metropolitan Project of Support for the CNI and the CIG, which led them to an even more solid organization that made it possible to resist the hard blow of the September 2017 earthquakes, which made the abandoned property located in 18 Roma Street, in Colonia Juárez completely uninhabitable. This was a place where many Otomi families lived, but after the earthquake, they camped around the property and were later violently evicted by riot police from Mexico City.

On October 12, 2019 (Columbus Day), when the CNI made a call to place on the peoples’ agenda the threat of mega-construction projects, the dispossession of territory and the murder of Indigenous peoples like the assassination of Samir Flores, they said “enough is enough!”. like the one that happened with Samir Flores. Then, after a consensual-vote-like assembly, the Otomí community thought about going to the monument to Christopher Columbus, located in the roundabout formed at the intersection of Buenavista and Héroes Ferrocarrileros streets in the Cuauhtémoc county of Mexico City, but they discussed it again and resolved that, due to the urgency, a more forceful action was necessary. After dialogues, discussions and proposals, they concluded not to go to the Columbus monument to tear it down, but to the Indigenous Peoples National Institute (INPI).

“For us there is an important experience that our Zapatista brothers taught us in 1994, and that we somehow associated to the emergency call made by the CNI to take a solid action that could make visible the dark side of that AMLO’s Inauguration Day with the presence of some indigenous peoples coordinated by the government,” says Filiberto Margarito Juan, another Otomí Councilor for the CIG.

The Otomí people emphasize that the INPI hosts those rigged consultations and as a way to impose the megaprojects. They do not doubt that it is from the institute that they are ordering the murders of the community environmental defenders. That was the fact that made them think that the best place to make their demands clear was from the federal headquarters, which, with about 600 employees, has a computer system that controls and manages all the information concerning the Native peoples of the country.

The Indigenous Peoples National Institute facility being occupied. Photo: Luis Alberto González.

At the INPI occupied place, there is a piñata today, celebrating the new year. A little girl invites us to stand in line to hit the piñata and grab some candies. She shows us how the piñata is hanging from a long lace in the parking lot of the institute. The community is there singing the “go ahead go ahead, don’t lose your mind, because if you lose it, you lose your way.” I keep thinking about the reason for this “piñata” song that we memorize since we were children, and that is that we can only walk if we do not lose the sense of constantly building a path on which we can walk; it is not about walking headed where we are told to, but walking from ourselves.

In the middle of the brainstorming inspired by the swing of the piñata, Diego García tells me about their findings when they took over the INPI headquarters. As it turns out, there is a series of protocols for fake consultations: “We have already seen how they are managing the issue of the Mayan Train, the Interoceanic Corridor, and so on, that is why we do not doubt that it is from this facility where they discussed how to get rid of our comrade Samir. It is risky to point it out, but you can expect everything from the State. As an example, we have the case of the 43 disappeared and that we still do not know the truth,” he clarifies.

Otomí Council Maricela and her Otomí comrades welcoming Hilda Hernández and Mario González, both parents of the Ayotzinapa disappeared student César Manuel González. Photo: Diego García.

The Otomí “Enough is Enough!” action was swiftly effective, without violence and peaceful. They asked the workers and police to leave, and then released a statement in which they specified their demands and formally declared that the facilities had been occupied. A hundred days after the occupation, they have registered 80 families living inside the institute. Another 20 families are taking care of the properties where they have survived these years. The little girl who invited us to play piñata says eloquently, innocently and friendly, “I don’t want to leave here, there are no rats and it’s warm!”.

Otomí girl. Photo: Luis Alberto González.

Thanks to all these actions of resistance, protest and dialogue, the government of Mexico City has recently announced that a decree will be published to expropriate the Zacatecas estate for the benefit of the Otomí community. They hope that the same will happen for the rest of the properties:

“We are waiting (between March-April) for the same to happen for Guanajuato and Zaragoza Streets. We are also estimating that the local government will confiscate the 1,500-meter land in 18th Roma Street and officially handed to the Otomí Community on August 13th, 2021, because it is the 500 commemoration of the fall of Teochtitlan City and the day when Zapatista comrades and Councilors of the CIG going in a caravan to Europe will symbolically arrive to the Spanish capital. Our authorities never do something good if it is not also politically convenient,” clarifies García Bautista.

Diego explains that the expropriation of this property must recognize that the Otomí community represents an icon of struggle and resistance in Mexico. “For us this property represents a possibility of decent housing, but also the preservation of memory, as it was the symbol of the Spanish resistance against Francoism and its genocidal policies. This building welcomed the exiles and refugees from the Spanish resistance, and it is the place where they planned insurgency actions against Franco’s dictatorship.”

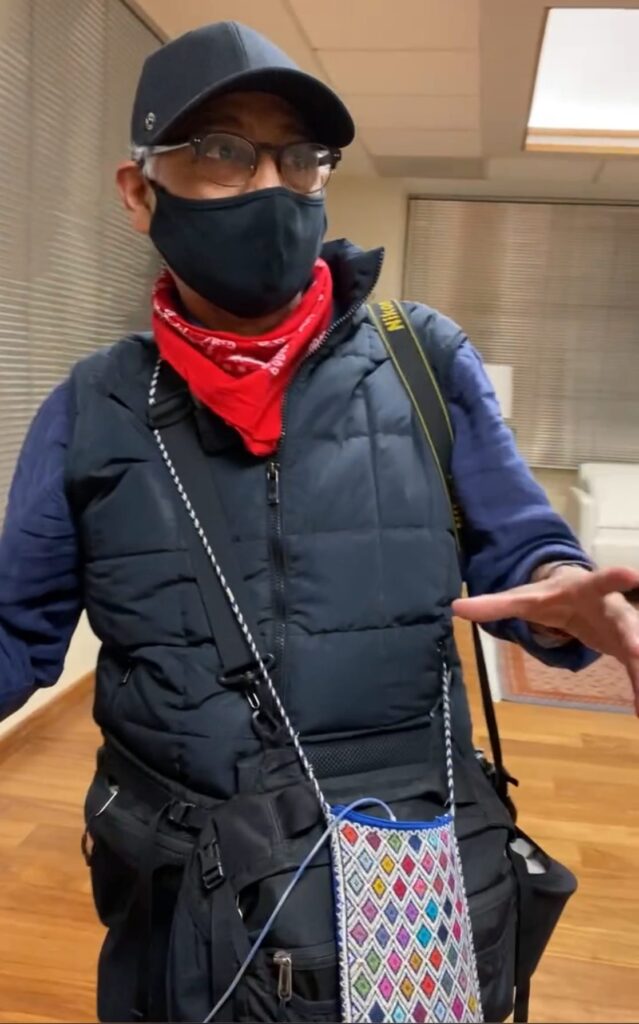

Diego García Bustamante (UPREZ Benito Juárez and Café Zapata Vive Founder) from inside the INPI being occupied. Photo: Luis Alberto González.

3.

And What About the Pandemic?

The INPI occupiers have very much in mind the sanitary controls. Before staring the occupation, in the process of organizing and consulting with the community, each and every one expressed the needs that an action of these characteristics entails. As a result of their assembly discussions, they agreed to create several committees in charge of security, food, cleaning, stockpile, finance and health. All this was agreed without even knowing what they would face inside the headquarters of the institute, but that the Otomíes were moderately perceiving when entering the 6-story building to analyze the space. They were able to access the site using different reasons – from an informative query, to some legal process, and so they began to record schedules, accesses, personnel and the orientation of some offices. Although it was impossible for them to have access beyond the first floor, that gave them enough clues of the general picture with which they were able to draw areas for the committees to work with.

“The Otomí families have been learning and getting informed on how to run each Committee in a functional and harmonious way. This means placing oneself on the facts and assuming responsibility at this level. Writing slogans on social media is one thing, taking action is very different. This building being a federal institute, we were worried about a possible violent eviction, since it represents a lot for the political system, particularly in the current government’s narrative, because this is the very icon of their imposition,” García Bautista clarifies.

The Otomí community participates in the Health Committee and their knowledge of traditional and alternative medicine is combined with that of modern medicine. That’s how so far they have been able to deal with the SARS-COV2 virus (known as Coronavirus). There have been no infections, not a single one. They are all seen wearing face masks (except the smallest to avoid suffocation as recommended by the World Health Organization). They keep a record of who should access, they have gel and cleaning protocol. However, Diego is honest – the community has little credibility in the virus, he says.

“Like many other Indigenous communities, the Otomí community no longer believes the government, so when this one releases recommendations, they consider them illogical. They say, ‘Where the hell are we going to wash our hands if we don’t have water? How can we keep social distancing if we live crowded in the street?’ The government is not believed [about the virus], but they did believed in it when the EZLN statement came out with the call to take care of themselves. That was the turning point,” says Bautista, while Councilor Maricela complements, “If our Zapatista comrades are so isolated but took security measures, and closed their territories, and are preventing outsiders from leaving or entering to protect life, as it is their guideline, then, we assume that.”

The facts are one hundred days without contagion, and little by little they have taken extreme measures – they are already planning to set an isolation area in case there is one who has symptoms and needs to quarantine himself/herself and being transfered to a medical institution. During this new pandemic pike at the beginning of 2021, those within the INPI were informed that they would not be able to go out to see their families in Santiago Mexquititlán as a precaution. Whoever decided to go see them could not return to the headquarters until further notice. Diego does not stop having a self-critical look on the matter and expresses that greater discipline is still needed from everyone, with greater responsibility to close the ranks of the virus.

We have to keep in mind that the police have not been able to get us out of here, but the virus can,” he says.

Otomí woman at the assembly. Photo: Diego García.

4.

An Otomí Doll and a Beetle

The Otomí people have installed a highly organized shop inside the institute’s building, from where they can manufacture handicrafts, mainly the iconic Otomí doll, the quintessential Mexican doll. This, along with fundraisings from civil and Indigenous organizations, is sustaining the protest movement.

“We have been able to set up a shop to make the Otomí doll, this iconic doll that is widely known in Mexico, with her colorful skirt, little black eyes, smiling mouth and braids linked with colored ribbons. In this shop we are making a new version of that doll as a unique symbol of this pacific occupation. It is an Otomí doll, in Zapatista version,” says Elvira, while she weaves the little legs of the iconic pepona, stuffed with cotton.

Work line for the Otomí doll. Photo: Diego García.

The sale of the doll is allowing an important income for the families’ survival. They also put on sale recently – after deciding it in their assembly – the handicrafts inside the institute, many of which were personal gifts made to the Native peoples to Adelfo Regino Montes – gifts to avoid that the top officer in turn forgets them, following a tradition that, shamefully enough, reveals the nepotism and the historical neglect of the government’s institutions.

“When we arrived at the INPI and began to walk through the floors asking the workers to leave, we realized that all the walls, furniture, desks, were saturated with handicrafts, many bottles of wine, mezcal and coffee. We ten looked at the contrast between the contempt for Indigenous communities and the presents they actually accept. They despise their physical presence, they do not listen to their demands and denunciations, but they do have this facility saturated with the artistic workforce of the towns throughout Mexico. There lies the inconsistency of the speech and the so-called ‘Fourth Transformation’ which, on the one hand, attacks Indigenous leaders defending the land and water, but widely and enthusiastically use Indigenous labor as decorative pieces.”

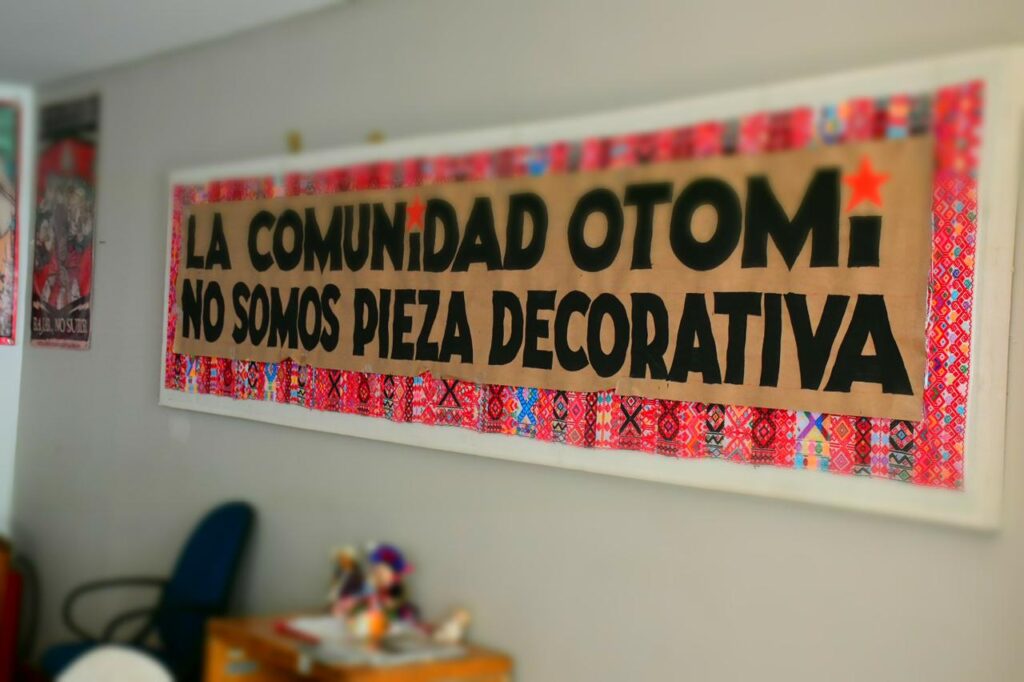

Through their assembly decision-making system, the Otomí community in resistance decided to remove all these works to put them on sale and raise funds. They called this symbolic action “The Traitors’ Expo-Sale,” which points to Adelfo Regino, who was one of the founders of the CNI, and whose actions are now repudiated by the Native peoples in resistance. The slogan of this expo-sale, emphasizes their commitment:

We, the Otomí community, are not a decorative piece.”

That’s how they denounce that Indigenous peoples should not be looked at in showcases just as part of the ethnography without endowing them with rights, “Regino has already forgotten that,” Councilor Maricela says.

From the hundreds of handicrafts that were gifts to Adelfo Regino, head of the INPI. Photos: Diego García.

This expo-sale is so that in some way, ordinary people, are the ones who can treasure these precious objects that symbolize a part of the worldview of the original communities, and not just someone in a position of political power. They want to re-virtue them while generating income to sustain two areas of their organization: (1) to continue promoting and sustaining the Otomí dolls’ manufacturing shop, and (2) to generate a fund for food, hygiene and medicines.

It is still to be seen if the government of Mexico City complies with the agreements for the expropriation of real estate, and if in some way the Federal Government manifests itself regarding the demands of the Otomí people in resistance. In the meantime, they make something clear:

“We repudiate what Adelfo Regino Montes and INPI represent for indigenous peoples. That is why we are in the bowels of the dinosaur who decides how and where to crush the Native peoples. We denounce the imposition of mega-construction projects of death and the militarization of Indigenous peoples, and the attacks against our Zapatista sisters and brothers, ordered by the interests of the Fourth Transformation,” clarifies the Executive Board of the Otomí community in resistance.

Otomí Assembly inside the INPI. Photo: Diego García.

Meanwhile, in this headquarters they take shelter from the winter; they have running water, thanks to the dialogue they have established with the government of Mexico City, to have healthy conditions while they wait for the resolution. There is also electricity (which stopped working just a couple of times). What the community buys with their funds are gas tanks and potable water to drink.

While thinking about what could be the menu today to feed the community, Councilor Maricela dreams that the authorities of Mexico and the world will listen to the call of the native peoples. That is why she also invests much time in preparing for the trip with the Zapatista caravan that will go to Europe next summer (if the pandemic protocols allow it). She will probably be making the trip as a representative of the Otomí community, calling for for tolerance, justice, democracy and freedom in the world. As Indigenous people from autonomous communities, they will test and put on the eyes of the plane: racism, transboundary, migration and feminism. These struggles have been accentuated nowadays and that have put the world in an unprecedented epochal change.

The Assembly inside the INPI is being visited by CNI lawyer Carlos González, Speaker María de Jesús Patricio, and journalist Luis Hernández Navarro. Photo: Diego García.

“With organization, work and patience, things that a beetle has taught us a lot, we will wait and see” concludes Diego García Bautista, as he smiles at me and hands me a paper with a handwritten note that until that moment he had stuck behind his work station:

Don Durito [the Zapatista beetle] used to say: ‘Clearly, there are at least two things above borders: one is crime that, disguised as modernity, distributes misery across the world; the other one is the hope that shame only exists when one misses a step at dancing, and not every time one sees himself in a mirror. To end the first one, we need to make the second flourish, you just need to fight and be better. The rest follows itself and is what usually fill libraries and museums. It is not necessary to conquer the world, just remake it. So that’s it. Wishing you good health. Keep in mind that a bed is only a pretext to love; a tune is just an ornament to dance; and nationality is only a merely circumstantial accident to fight.’”

The president’s statuette is still there, broken, battered, without the arm that claims to serve the nation. The Otomí community was sworn instead. They demand respect to the diversity of their requests and hopes for all indigenous nations, instead of being imposed to them.

Young Otomí. Photo: Diego García

♥Do you want to DONATE to this amazing Otomí Pacific Occupation of the fake Indigenous Peoples National Institute (INPI)? You can do it (without intermediaries) at this direct link: ApoyoComunidadOtomi

♥Do you want to chip in with some dollars so that independent journalism like Rip.mx keeps existing? Please go to:

Making Cultural Guerrilla

Your help means the world to us!

Leave a Reply